Learning to participate as an effective

listener and contributor during discussions isn't easy.

At times, we all may have difficulty listening well to others and

contributing our own ideas. Finding meaningful things to say

about what theyíve read, as well as participating as an active member

of the discussion, requires skills that many students have not yet

developed. Therefore, the time and effort you invest in teaching

and practicing, the process of discussion will pay crucial dividends.

Learning discussion skills can be

broken down into three components: Knowing what you're aiming

for (what makes a good discussion), experiencing it either directly

or vicariously, and developing some guidelines.

Above all -- students need to practice,

practice, practice. Students will grow in their ability to

discuss gradually -- it will take time. Be patient

with them and with yourself. One of the fastest ways for students

to improve in the quality of their discussions is to build in regular

debriefing sessions.

Return

to Making Discussions Work

Identify the Elements of a Good Discussion

This is a great place to begin for the simple reason that students

-- at all levels -- know what goes into an effective conversation

(even if they can't yet do it). Here are several ways

to find out what your students know about good discussion:

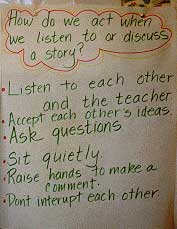

- Brainstorm Your

best bet is to ask your students -- and then make a chart of what

they say. This can be the beginning of your guidelines

for discussion. For example, Vicki

Yousoofian's first graders gave her all of the information

she needed for the chart below when she asked them, "How do we

act when we listen to or discuss a story?"

- Discussion Etiquette

This is a focused form of brainstorming. Fifth grade

teacher, Kirstin Gerhold

wanted her students to understand the elements of good discussion.

For example, she wasn't sure they really knew what being an "active

listener" meant. Kristin discussed with her students what

each element of discussion "looks like" and "sounds like" using

the chart below. She identified the elements of discussion

etiquette along the left-hand side, then asked her students to

tell her, "What would it look like and what would you hear if

someone were truly an active listener?"

Kristin listed the

Discussion Elements -- her students came up with

the descriptors under

"Looks like" and "Sounds like".

|

Discussion Elements |

Looks Like |

Sounds Like |

|

Active Listening |

Eyes on speaker

Hands empty

Sit up

Mind is focused

Face speaker |

Speakerís voice

only

Paying attention

Appropriate responses

Voices low

One voice at a time |

Active Participation

(respond to ideas and share feelings) |

Eyes on speaker

Hands to yourself

Hands empty

Talking one at a time

Head nodding |

Appropriate responses

Follow off othersí ideas

Nice comments

Positive attitudes |

Asking Questions

for Clarification |

Listening

Hands empty |

Positive, nice

questions

Polite answers |

Piggybacking

Off Others' Ideas |

Listening

Paying attention |

Postive, nice

talking

Wait for people to finish |

|

Disagreeing

Constructively |

Nice face

Nice looks |

Polite responses

Quiet voices

No put downs |

Focused

on Discussion

(body posture and eye contact) |

Eyes on speaker

Hands empty

Sit up

Face speaker

Mind is focused |

Speaker's voice

only

Appropriate responses

Voices low |

Supporting

Opinions

with Evidence |

One person talking

Attentionon the speaker |

One voice |

|

Encouraging

Others |

Prompt people

to share

Ask probing questions |

Positive responses |

Return

to top

Experience Discussion

There is no better teacher than actual experience with discussion

to help students internalize what works -- and what doesn't.

This is how students move from knowing what goes into discussion

to being able to participate effectively as a group member.

We suggest two ways to begin: Direct experience (immersion)

and vicarious experience ("fish bowl").

- Immersion

(or how to learn by jumping in) This strategy operates

on the principle that before students can generate effective guidelines

for discussion, they need to experience it first-hand. The

immersion strategy does just that: Students carry on a brief

discussion even before you've talked about what makes a good discussion

-- and afterward they have a true "need to know."

For example, Lori

Scobie knew that her fourth graders would have far greater buy-in

for discussion guidelines if they could see a real need for them.

She believed that immersing her students in a discussion was the fastest

way for them to learn what guidelines they needed. What happened?

Well, the inevitable: Someone had trouble moving his chair to

his group without stepping on toes; a student gave away the "good

part" of the book that others hadn't yet read; someone else wouldn't

say a work -- or talked all the time. After students had met

in their groups for about ten minutes, Lori gathered everyone in the

front of the room. Writing their responses on a large piece

of chart paper, Lori asked them what they liked about meeting in groups

for literature circles. Here's what they said:

Sharing feelings about the

book.

We shared if we liked the

book or not.

We got to talk about different

parts of the book.

Then she made another column on the

chart, "How can we improve?" Here's what went on that

list:

Some people can't read as

fast as others

Not interrupting

Trying not to goof around

Working together

Getting started right away

Talking more; some talked

a lot and some didn't talk very much

Next, she explained that it was time

for them to develop guidelines.

- Fish

Bowl Perhaps the most powerful way for students

to understand what goes into a good discussion is to observe one

in action. If you have students in your classroom

-- or even students in other classrooms -- who are discussion

veterans, perhaps they can be models. Several of Janine

King's sixth graders had participated in literature circles

the year before. She used a common cooperative learning technique

-- a "fishbowl" -- to model good discussion strategies for the

rest of her class.

Just as Lori Scobie

did with the immersion session session described above, Janine presented

a discussion model after students had experienced one literature circle

cycle with Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry (Taylor, 1976).

That way, she knew her students had a frame of reference to understand

what they would see -- and they had a clear need to know. Janine

invited five students with strong discussion skills to participate

in the demonstration. She asked each to re-read the last chapter

and gave them the prompt, "Look

for something to talk about that stood out for you". For

the demonstration, the group gathered chairs in a circle at the front

of the room and began to talk. Although understandably self-conscious

at first, the students quickly forgot the audience and engaged in

an interesting discussion of the book's ending. From

this experience, Janine and her students developed their guidelines.

Return

to top

Develop

Guidelines

Guidelines for discussion

work best when they're developed jointly with your students.

You can do this after either an "immersion"

or a "fish bowl" experience as described above.

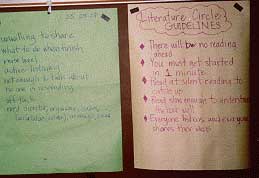

- After

an "immersion" experience: Pointing to each comment

on the chart (see green chart below), Lori asked for a positive

way to phrase it. For example, she began with the statement,

"Some people can't read as fast as others." Carolyn suggested

that they needed a guideline about not reading ahead, since those

who knew what had happened sometimes told -- spoiling it for those

who hadn't read as far. Several students agreed that this

was a big problem. Lori asked, "Since this seems to be a

real concern, is there a positive statement we can make for this

guideline?" Mobi offered, "There will be no reading ahead."

Ashley then pointed out that some students have a hard time reading

as fast as others. The class shaped another guideline:

"Read during silent reading to catch up." After about 20

minutes of negotiation, the guidelines list was finished.

The chart below

shows two lists : The first: "What went well and what

do we need to work on?" The second: The final set of

guidelines. As you can see, the list is short. Lori

kept the number of items limited to those she felt were most important.

Although she may have had additional guidelines in mind, she was

willing to begin with these -- they covered everything that was

crucial.

|

Step

1 (green chart)

What went well; What do we need to work on?

- people were unwilling

to share

- we didn't know what

to do when finished

- noise level

- active listening

- not enough to talk

about

- no one is responding

- off task

- need director, organizer

or facilitator

Step 2

"Literature Circle Guidelines"

- There will be no reading

ahead

- You must get started in 1

minute

- Read at silent reading to

catch up

- Read slow enough to understand

the book well

- Everyone listens and everyone

shares their ideas

|

Step

1 (green chart)

What went well; What do we need to work on? |

Step

2 "Literature Circle Guidelines" |

Process

of developing discussion guidelines:

Step 1: Brainstorm from experience: "What went well

and what do we need to work on?"

Step 2: Word guidelines as positive statements

-

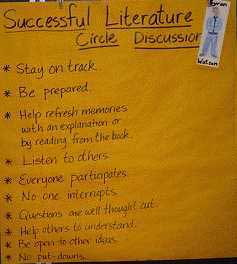

After

a "fish bowl" experience: When the fish bowl demonstration

was over, Janine asked, "What did you notice as you watched

this discussion?" This generated a flood of responses.

Because the discussion had taken place right in front of them,

the students had no trouble picking out what worked. Janine's

class generated the same kind of list as Lori's fourth graders

did -- and from their list grew the guidelines (see below) that

they used for the rest of the year. Janine says the fishbowl

technique made a big difference in her students' understanding

of how to discuss: "That was the big toe in the water

for us before we put the whole foot in."

Discussion guidelines

after a fishbowl experience

Return

to to

|