| Literature Circles Resource Center | |

| home | structure | books | discussion | written response | themed units | extension projects | |

|

|

| Choosing

Books for

Literature Circles Adapted from Chapter 4 Getting Started with Literature Circles by Katherine L. Schlick Noe and Nancy J. Johnson ©1999 Christopher-Gordon Publishers, Inc. |

Selecting books that spark students' interests and make them want to discuss and respond is a key component of successful literature circles. Under "How Teachers Choose," we offer guidelines on identifying, obtaining, and working with books for literature circles. Under "Student Choice" you'll find suggestions for helping your students learn to make good book choices for themselves. Click on "Good Books for Literature Circles " for links about sources of great books for literature circles.

Teacher Selection: As you select books for literature circles, here are some considerations to keep in mind: Qualities of a Good Literature Circle Book A good literature circle book touches something within the reader's heart and mind and compels response. You can use some fairly simple criteria to help you find such books. For example, consider these three questions: "Does the book succeed in arousing my emotions and will it arouse children's emotions? Is the book well written? Is the book meaningful?" (Monson, 1995, p. 113).* In short, a good literature circle book has substance -- something worth talking about. In addition to content, consider a book's layout -- number of pages, size of print, inviting space on the page, use and placement of illustrations. These can be crucial deciding factors for students as they choose a book. If the configuration of pages and print is too overwhelming, a book may seem insurmountably difficult even though its content is riveting. As veteran teacher Dan Kryszak says, "You can tell a well laid-out book, as if it says, 'Hey, I've got a great story. Come on in and relax and enjoy it' not 'Here it is -- BAM. Hurry up or you'll never finish!'" How can you tell if a book will work? Here are some specific considerations that teachers make when choosing books for literature circles:

It's important to accept that the first few times, you may not be able to find "perfect" literature circle books -- sometimes you just have to start with what you can find. Here are some possible ways to choose your first literature circle books:

Journals Professional journals that provide book reviews include Book Links (American Library Association); The Horn Book Magazine; monthly columns in TheReading Teacher and Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy (International Reading Association), Language Arts (National Council of Teachers of English), and The New Advocate (published by Christopher-Gordon Publishers, Inc. 800-934-8322).Meeting a Range of Reading and Interest Needs Does

this sound familiar: "What is a good third grade book?"

Or how about this: "I teach sixth grade, and my students

read anywhere from first grade level through high school.

How am I going to find books at all those levels?" Determining

How Much to Read Structure

Time for Reading

Teachers use some or all of the following ways to obtain multiple copies of books for literature circles:

Return

to Structure: General Guidelines: Reading

Student

Choice Teach

Students How to Make Good Book Choices

We've all had students who chose a literature circle book for

the reason that Hannah did: "Out of all those books, it

was the only one calling my name." Students may need guidance

to select books that call their names as well as books that they

can read. Help students understand that making

effective choices goes beyond finding the shortest (or longest)

book. Selecting a book that holds your interest and gives

you something worth discussing with others is part of becoming

a critical reader. During

their book talks, many teachers set the books on the chalk tray

or on a table, arranged according to difficulty. You do

not need a readability formula to tell you how difficult a book

will be for your students to read. Examine it. Flip

through the pages. Look at the language, typeface -- even

the size of the print. Ask other teachers and students what

they would say about its level. These informal -- and quick

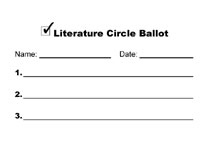

-- assessments can give you the information needed. Provide Choice Most teachers discover that the best way to engender ownership and "buy in" for literature circles is to give students choice in the books they read. No matter what books you have chosen, scrounged, or discovered -- allow students to select the one they want to read. A key element of choice is offering a range of books that fit what you know about your students' abilities and interests. If your overall goal is for students to delve deeply into a book and construct meaning collaboratively with others, you'll probably want the groups to be heterogeneous by gender, experience, and ability -- keeping students' choice as a high priority. Introduce Books Through Book Talks Informal introductions invite students to select and read a book by sharing just enough information to entice them without giving anything away. You might read aloud a short selection to give students a sense of the language and story. Better yet, ask students who have already read the book to give the book talk. This will be easier and more effective later in the year as more books have been read in your classroom. Build in Time to Preview the Choices Many teachers provide time for students to sample the book choices as they decide which one they want to read. If you give the book talks in the morning, for example, you might leave the books out during recess and lunch so that students can do a "hands on" perusal. Allowing enough time at this point is an effective way to honor your commitment to choice. Students Select First, Second, and Third Choices When students are ready to choose, distribute either pre-printed ballots or small pieces of blank paper on which students write their name and list one to three book choices (see ballots below). The key here is to help students understand that their first choice is the book they most want to read; their second and third choices should also be books that sound interesting and that they would be able to read if they cannot have their first choice. Form Groups Although student choice is at the core of literature circles, it is really choice with teacher guidance. You know your students well, and you should take the lead in forming the groups, taking into consideration what your students have chosen. Four to five members is an ideal group size -- enough to generate discussion but not too many to stifle individuals. Janine King uses a simple and effective method for forming groups in her sixth grade classroom. The process takes about 10 minutes and can easily be done while students are at recess. She spreads out the ballots on a table to get an overview of which students have selected which books for their first choices. She writes the book titles on a tablet with five |